Glimpses of British History

Early Britain

The British Isles probably have a much longer history than is commonly believed. There are remains of Stone Age life dotted all over Britain and Ireland. They are especially abundant in the Orkneys, where numerous mounds, graves and great circles of standing stones can still be found. There is also a neolithic village called Skara Brae, one of Europe’s most perfectly preserved Stone Age villages. It has been in the Orkneys for five thousand years, and was uncovered by a ferocious sea storm in 1850. It is now thought that by 1000 B.C. Britain was a crowded island with probably as many people living there as in the 16th century A.D. The greatest monuments of those times are the great stone circles – the largest at Avebury, Wiltshire, and the most spectacular of all at Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. [1]

Stonehenge

The first document in the written history of the British Isles is a passage which records the visit to the Cornish peninsula of a Greek sea captain, Pytheas of Marseilles, about 320 B.C. At that time Britain was inhabited by the Celts. They were tribes from the upper Danube, who eventually settled in Italy, Spain and Britain. The Celts were an agricultural people who lived in farmsteads or villages. By the standards of those times, they were a rather advanced people, who could spin, weave, make pottery and metal items. They arrived in Britain from about 700 B.C. quickly taking over from the peoples who were already there. The Celts were divided into three classes: the nobles, whose task was to fight; the Druids, who acted as judges, teachers and dealt with the gods by means of magic; and the vast mass working on the soil.

For about 600 years the Celts lived in peace until, in the middle of the first century B.C., Julius Caesar decided to invade the island. The first time the Romans landed in 55 B.C., then again – in 54 B.C., when they pushed northwards, crossing the river Thames and conquering the whole of the south-east. Finally they made peace with the Celtic chiefs, who handed over hostages and promised an annual ransom.

The next major invasion came in 44 A.D. (Anno Domini, in the year of Our Lord), and then in 77 A.D. Britain became a province of the Roman Empire. The Roman governor Agricola advanced and conquered Scotland. For the first time the whole island was under single rule and to celebrate this a vast triumphal arch was built at Richborough. Eventually, however, Scotland was abandoned, and in 122 the Roman Emperor Hadrian came to Britain and ordered the building of a wall 80 miles long, across the northern border, in present-day Northumberland. Every 15 miles there was a fort and between each fort there were two watch towers. On the enemy side there was a ditch for protection, and a second one on the Roman side to facilitate the transportation of supplies. The wall was a remarkable achievement and much of it still stands.

From the middle of the 2nd century it makes sense to talk about a Romano-British culture. The Romans brought with them a number of profound changes, the greatest of which was the introduction of towns. Urban life was essential to them, but totally new to the Celts, who lived in scattered enclosures. Each Roman town had its own public baths, often several of them, with elaborate changing rooms, a gym, and cold, warm and hot baths. The Romans were masters in handling water; they built splendid aqueducts, drainage and sewerage system. Each town also had its own amphitheatre on the outskirts. Initially the towns were built without walls, but later, as the threats of invasion multiplied, they were added. Many modern British city names come from the Roman times: Gloucester, Leicester, Worcester, Winchester, and Chester. All these names are formed from the Latin word castra, which means an armed camp. One of the most spectacular Roman towns is Bath. Constructed over a hot spring that gushed water from underground, Bath was at once a marvel of hydraulic engineering, a showy theatre and a mysterious cult, a typical Romano-Celtic town. [3] In Dover the Romans built a 96-bedroom hotel, the last word in luxury.

The Romans also reorganized the countryside by building villas. Villas began as modest farmhouses, but as time passed they became more luxurious, some of them were virtual palaces with comforts like under floor heating, mosaic floors and wall paintings. Just how numerous these villas were is revealed by the fact that archaeologists have discovered the sites of about 1,000 villas on the British Isles.

Roman Britain was held together by a strong system of government. The creation of towns and villas formed a ruling class that included Celts, who were romanized, lived in towns and spoke Latin. In the country Celtic survived as the language of the peasantry.

The Romans introduced new vegetables and fruits: cabbage, peas, apples, plums, cherries and walnuts. They were the first settlers on the British Isles who made formal gardens, in towns and around villas, and brought the domestic cat.

The Romans were tolerant in matters of religion, except in the case of cults that involved human sacrifice. The Druids used to burn people alive to mollify their gods and this practice was suppressed. Otherwise the Celtic gods lived on side by side with the Roman ones, the most important of whom were Jupiter, Juno and Minerva. The Roman temple built at Bath, for example, was dedicated to both the Roman goddess Minerva and the Celtic water deity Sulis. Christianity also reached Britain. Its early history is extremely obscure until, at the beginning of the 4th century (in 313, when the Emperor Constantine was converted) [5] Christianity became the official state religion of the Roman Empire. In 314 the bishops of York, London and Lincoln went from England to a Council of the Church held at Arles. In 391 the Emperor Theodosius ordered the closure of all pagan temples. It is likely that many later Anglo-Saxon churches in fact go back to the Roman period.

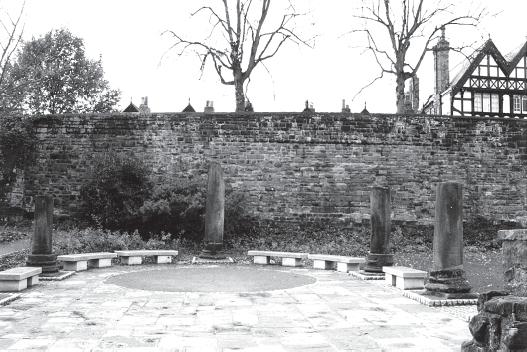

The Roman Garden in Chester

All in all, the Romans left an indelible legacy, one which contributed to the shape of what was to become English civilization, for the Romans never quite conquered the Celtic territories of Cornwall, Wales, or Scotland. The English language is unique among its Germanic cousins for the very large number of words which came into it from Latin.

When the Romans went they left behind a leaderless and defenceless people (in fact the Emperor Honorius sent his famous directive telling the British that they must now defend themselves), and these were no match for the fierce tribes that came to the British Isles. However, the change of civilization didn’t occur overnight. It was only by the 6th century that a different map of Britain began to emerge, one made up of a series of small independent kingdoms. The long process by which Roman Britain moved into the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms was a gradual one of adaptation. For a long time the Anglo-Saxons were a tiny minority that lived in the midst of an overwhelmingly Romano-Celtic population.

Invaders came from every direction. There were the Scots from Ireland who attacked the west, the Picts from the far north who penetrated south, and the Anglo-Saxons who landed in the south-east and East Anglia. The Anglo-Saxons were made up of various tribes who came from an area stretching between the mouths of the rivers Rhine and Elbe. A group of them was called Engle and from that came the word England. The Anglo-Saxons were pagans who worshipped gods such as Woden, Thor and Freya, whose names were to give the English language the words Wednesday, Thursday and Friday. The Anglo-Saxons had no interest in the Roman way of life, their society was differently organized. At the top came the nobles who fought, next the ceorls (freemen) who farmed and, at the bottom, slaves. The Anglo-Saxons didn’t live in towns, but in wooden huts. Their whole existence was war. Fighting bound them together in ties of loyalty to their leader. Loyalty was seen as the greatest of human virtues and the most detestable of all crimes was the betrayal of a king.

The Angles and Saxons took possession of all the land as far as the mountains in the north and west, and divided it into a handful of small kingdoms. In the south-east there was the kingdom of Kent and the south Saxon kingdom (Sussex), in the east – the kingdom of East Saxons (Essex), in the Midlands – Mercia, in the north – Northumbria, in the south-west – Wessex. Eventually the Christian Celts were wholly defeated; those who escaped death were pushed back into the mountains of Wales and Scotland, and also to Ireland, where their languages – Welsh, Gaelic and Erse – can still be heard.

In 597 Pope Gregory sent a mission to convert the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity. It is believed that the mission was inspired by the pope meeting a group of fair-haired youths in Rome. He asked them who they were and what their country of origin was. They answered that they were Engles, Angli in Latin. The pope is said to have remarked that he saw them not as Angli, but Angeli, that is angels. The papal mission was led by St. Augustine, and the missionaries made their base at Canterbury. The king of Kent, Ethelbert, fearing magic, insisted that his meeting with the missionaries take place beneath an open sky. Out of this came the grant of a place in Canterbury in which they could live and had permission to preach. Soon there were many converts, old churches began to be restored and new ones built. After a year Ethelbert himself became Christian. Augustine was consecrated Bishop and later Archbishop of Canterbury. Yet, that mission was only the beginning of the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons, a task that took most of the 7th century to achieve.

Monasteries such as Canterbury became centres of teaching and learning, where both Greek and Latin were taught, as well as so called Seven Liberal Arts that included the trivium – grammar or the art of writing, rhetoric or the art of speaking and the dialectic, the art of reasoned argument – and the quadrivium – arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. The most famous of all these scholars was the monk Bede (better known as the Venerable Bede), who wrote the History of the English Church.

Thus, by the 8th century a new society, deeply Christian, had come into being, only to face a new wave of invasions as fierce Northern people, the Vikings, began to attack from beyond the seas.

The story of Viking invasions is dramatically told in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, which traces how these raids accelerated during the second half of the 8th century. The Vikings were a people from Scandinavia, mainly Norway, Sweden and Denmark, whose life originally consisted in working the land and fishing, but who went on to attack and later settle in Britain, Northern France, Russia, Iceland and Greenland. One of the basic reasons for their endless raids was that their homelands no longer produced enough to support them. Another was the nature of their society that glorified fighting. The Vikings were pagan and believed that the gods rewarded fighters above all and that bloodshed and death in battle were the true paths to wealth and happiness.

One by one the kingdoms of the Anglo-Saxons fell until there was only Wessex left, where a young man called Alfred came to the throne in 871. [15] During his reign, which lasted almost thirty years, the advance of the Vikings was stopped and the foundations of what was to become the kingdom of England were laid. We can easily trace where the Vikings settled, areas of the country known as the Danelaw, by the endings to the place names. Whereas the Anglo-Saxon endings were ‘hams’ and ‘tuns’ (homes and towns), the Vikings had their ‘bys’ and ‘thorpes’.

After being defeated by Alfred, the Vikings held the north and East Anglia, while the kingdom of Wessex gradually expanded to embrace all the southern Anglo-Saxons. In 886 Alfred captured London. In the peace he made with the Danish king the English and the Danes were accepted as equals and for the first time there is reference to ‘all the English race’.

Alfred took important steps to ensure the defence of his kingdom. He realized that the Anglo-Saxons must develop sea-power, so he ordered the construction of warships. Even more important was the building of a network of defended enclosures, ‘burhs’, in which people could seek safety along with their goods and cattle. These were strategically placed and were either on the site of old Roman towns or carefully chosen to be new ones. We can trace many of them today in place names that end in ‘borough’.

Alfred was succeeded by three strong kings who took up the task of creating and consolidating the new kingdom of England. His son Edward the Elder first reconquered the whole of East Anglia and the eastern Midlands and then, by 920, all the lands as far as the Peak District. During the reign of Alfred’s grandson Athelstan the Viking invasions renewed, with the aim of setting up a northern kingdom based in York. In 927 Athelstan defeated them and soon established himself as a single king ruling both north and south, in effect the first king of England as far as Northumbria. A single currency was introduced for the kingdom and many new laws were made. During the reign of Edgar (959–975) the Roman-style ceremony of crowning and anointing the king appeared. In this ceremony it wasn’t the crowning by the bishop which was the most important act but the anointing of the king with holy oil in the same way as priests were anointed. This act set him apart from ordinary men, making him Lord-anointed. Yet, in spite of the king’s enhanced status and the mystique surrounding the monarchy, one of the fundamental principles of Anglo-Saxon society, which was to run down through the centuries, was that effective government should be based on a dialogue between the ruler and the ruled. At the top level it was reflected in the fact that Anglo-Saxon kings were always elected, from a member of the royal dynasty. That was the task of the great magnates, both nobility and upper clergy, who made up the king’s council called Witenagemot (from witena: Old English genitive plural of wita ‘councillor’ + gemot ‘meeting’). Also, all the English counties and shires took shape during this period; they were divided into smaller units called hundreds, each one of which had a kind of court (moot), where justice was administered by the king’s representative together with those who lived in the area.

Another fundamental principle of Anglo-Saxon England, which was to be important for the future, was that the kings were expected to live ‘of their own’, that is from the income received from the vast estates which they held as the country’s richest landowner. At the same time a system of universal taxation gradually began. This was the direct result of the attacks by the Norsemen that resumed under the weak king Ethelred, who decided to buy off the invaders with large sums of money called ‘Dane-geld’. Everyone had to contribute towards this; the money was collected from all over the country in carts and delivered to the king’s treasury at Winchester, the capital. Although these taxes were the result of a crisis, they set a precedent: everyone should be taxed to meet certain common needs such as war. Yet, since the kings were expected to live ‘of their own’, taxation was to be exceptional for many centuries, and was perceived as such by the people.

In the early 11th century the country was scourged by a new wave of Vikings, the Norsemen.

In 1009 Sweyn, king of Denmark, landed at the head of a vast army and by 1013 all the nation regarded him as full king. Ethelred fled into exile. But then Sweyn died and in the confused period that followed Ethelred died too. His son’s reign lasted for just seven months, and after his death the Witenagemot elected Sweyn’s son, Canute, to be king (1016–1035). Thus England entered the 11th century as part of a huge Scandinavian empire which embraced Denmark, Sweden and part of Norway. Canute, who had begun his life as a bloodthirsty warrior, transformed himself into an ideal Anglo-Saxon king. His greatest innovation was to divide the entire country into four great earldoms each presided over by an earl.

In 1042 Ethelred’s son Edward came to the throne as Edward II, often referred to as Edward the Confessor. He was a competent and wise monarch, ruling England for twenty-four years and leaving a united country to his successor. Edward the Confessor was a deeply pious man, and it was in his reign that Westminster Abbey was constructed. On his deathbed he nominated his brother-in-law Harold, Earl of Wessex, as his heir. After Edward’s death Harold was duly elected by the Witenagemot. He was a man of strong character and a brilliant soldier, so everything seemed to indicate that the Anglo-Saxon kingdom would continue as before. However, there was another claimant to the throne. He was William, Duke of Normandy (a duchy in Northern France). William’s claim to the Anglo-Saxon throne was in fact extremely remote, he was just a great-nephew of Edward’s queen, but he maintained that Edward himself had promised him the crown as early as in 1051, and moreover Harold had sworn allegiance to him as his future king during his visit to Normandy in 1064. The latter visit is surrounded by mystery and there is nothing to prove William’s claims beyond his assertion. Anyway, in the second half of the 11th century the Normans had a vitality that other peoples lacked. William was also a master of propaganda and diplomacy. He succeeded in persuading both the Holy Roman Emperor and the pope of the justice of his cause. Harold, on the other hand, was at a disadvantage, for, being threatened by the Norwegians and his own brother Tostig in the north as well as the Normans in the south, he had to fight on two fronts. When the Norwegians were defeated and Harold faced William in the battle of Hastings, which took place on October 14 1066, his army was exhausted. During the battle Harold perished, felled by a mounted knight with a sword. His army fled. The battle was to be an opening chapter in the story of the death of Anglo-Saxon England. Soon the whole of the south-east surrendered to William. On Christmas Day William was anointed and crowned in Westminster Abbey as William I (1066–1087). Although the conquest of England wasn’t achieved overnight, within five years, by 1071, William’s ruthless and efficient military machine had made the conquest an irreversible fact.

There is an interesting and unique historical document telling the history of the Norman Conquest, which is at the same time an example of political propaganda of those times. The Bayeux Tapestry was made between 1070 and 1080, commissioned by William’s half-brother, Odo of Bayeux. It is 70 metres long and 50 centimetres wide. The embroidered tapestry shows the events from the times of Edward the Confessor to the death of Harold. The scenes include, for example, Harold swearing an oath to William in Normandy, Harold breaking the oath by accepting the crown on Edward’s death, with a comet appearing in the sky foreboding disaster for the oath-breaker (the comet actually appeared on the night of 24 April 1066); William landing in England and the battle of Hastings in action. The underlying message of the tapestry is that perjury draws divine retribution on the person committing it: the defeat and death of Harold are presented as Acts of God.

The House of Normandy

As soon as it became clear that the king’s initial desire to work with the old Anglo-Saxon aristocracy had failed, he set out to create a new йlite that would be loyal to him and ensure his position as king of England. That was secured by two things: castles, and knights to man them. The most famous of all the castles was the Tower of London. William I organized the government of England on the system that had been successful in Normandy – the feudal system based on the ownership of land. He granted lands confiscated from the defeated aristocracy to 170 of his followers who became thereby his tenants-in-chief. The grants of land were usually scattered through several shires. Collectively each group of lands was called an honour and each honour consisted of several smaller units called manors, divided among the 5,000 knights who had fought at Hastings. A knight had to swear loyalty to his lord. Each tenant-in-chief had 2 groups of knights: one consisting of those who were permanently part of his household and a second one including those who came in return for land. The lords themselves had to swear loyalty to the king and to supply knights for his service. The common people belonged to the knight on whose manor they lived. They had to serve as farm-workers but not as soldiers. There was also a small class of freemen, who didn’t have to work on the knight’s farm. William was a strong king and the system worked. The trouble was that under a weaker ruler the system could break down, leading to private castles and armies.

The White Tower in the Tower of London

The same revolution was applied to the Anglo-Saxon church. In Normandy William controlled all the appointments of bishops and abbots, filling them with his own friends and relations. Bishops and abbots from before 1066 either died or were deposed. They were replaced by Normans, and had to render the king rent in the form of armed knights. Together the tenants-in-chief, bishops and abbots made up the new ruling class, for the higher clergy, being educated, were essential for the running of the government. In these changes William was aided by a new archbishop of Canterbury, Lanfranc. Both believed that priests should be celibate. More significant for the future was the creation of special courts to deal with church cases only.

All the lords had the right to attend the king’s council and it was his duty to ask their advice. William held council meetings nearly every day, wherever he happened to be. Three times a year he held a ceremonial council for Christian feasts and wore his crown: in Winchester for Easter, in London for Whitsun and in Gloucester for Christmas. Then every lord had to attend.

Winchester castle was still the seat of Government. Here William set up his government office, which controlled the collection of taxes and kept account of all expenses. From this office men were sent out in 1086 to make a detailed record of all the wealth of England, for William, fearing invasion from Denmark, wanted to extract the maximum in taxation. The result was the Domesday Book, which gives us a complete description of the country. The book occupies 400 double-sided pages and paints a picture of a country where virtually the entire population was engaged in agriculture with little or no industry or commerce, and few towns.

William’s reign saw a wave of new building in the beautiful style called Norman or Romanesque. The Romanesque style was fully developed by about 1100, becoming the accepted style for church buildings throughout Europe, with marked regional variations. In England, soon after the Norman Conquest work began on the Cathedrals of Canterbury, Lincoln and Winchester [12], and the churches of St. Albans, Ely and Worcester. However, only parts of these buildings have survived: they were all largely rebuilt in the 12th – 14th centuries. The finest Norman building to survive in England is Durham Cathedral, begun in 1093 and completed in 1133. [7] The style made use of massively thick walls, huge columns and lofty vaults. There were small windows and doors. The round arch became established as the basis of the church interior. [9] Some of the churches were indeed very ornate, with decorated pillars and carved doorways.

William’s reign saw a wave of new building in the beautiful style called Norman or Romanesque. The Romanesque style was fully developed by about 1100, becoming the accepted style for church buildings throughout Europe, with marked regional variations. In England, soon after the Norman Conquest work began on the Cathedrals of Canterbury, Lincoln and Winchester [12], and the churches of St. Albans, Ely and Worcester. However, only parts of these buildings have survived: they were all largely rebuilt in the 12th – 14th centuries. The finest Norman building to survive in England is Durham Cathedral, begun in 1093 and completed in 1133. [7] The style made use of massively thick walls, huge columns and lofty vaults. There were small windows and doors. The round arch became established as the basis of the church interior. [9] Some of the churches were indeed very ornate, with decorated pillars and carved doorways.

As for domestic architecture, there were manor houses and castles. In early Norman England the hall, together with a few out-buildings about a courtyard constituted the entire accommodation of the manor house. The first castles had a mound or motte [6] (in modern England remains of more than 3,000 Norman mounds can be found) with a single defensive four-storey tower and a bailey, that is a fortified outer wall initially made of wood and later of stone. The most famous of the early Norman towers is the White Tower of London begun in 1078. Slightly later came circular shell-keeps like that at Windsor Castle. In the mid-12th century this style changed under the influence of the Crusades. A fine example of the new style is Conisborough Castle built about 1180 (used as a setting for the film based on Ivanhoe by W.Scott). The tower or the keep was retained as a lordly residence. [14] This was surrounded with a stone curtain wall with solid half-round towers along its length. Rings of concentric defenses were to be the future of the castle form. [13] By the second half of the 12th century the castle had already become primarily a domestic residence, but with built-in precautions for protection against social unrest.

For the invaders the conquest of England was a remarkable achievement, and enduring at that. For the native population it was a cruel and humiliating defeat which swept their civilization away. The new aristocracy saw its first loyalty not to the land they had conquered but to Normandy. For four centuries to come English kings were also to be continental rulers, and the wealth of England was expended in wars aimed at acquiring, defending and sustaining a mainland empire.

The state which William I created called for strong kings. Fortunately he was succeeded by two of his sons who were just such men, but disaster was to strike later when his grandson seized the throne. The crown passed first to the king’s second son, William Rufus, next to his fourth son Henry I, and finally to his grandson, Stephen. Stephen was a weak king, so the result was anarchy. Some of the barons went over to Matilda, the daughter of Henry I, others were loyal to Stephen. Worse, the barons began to fight private wars with each other.

Medieval England

Before his death in 1154 Stephen adopted Henry, Matilda’s son, as his heir. Henry’s father was Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou, Matilda’s second husband, and his wife was Eleanor from Aquitaine. So, when he came to the thrown as Henry II (1154–1189) he held an enormous empire including England, Normandy, Brittany, Anjou and Aquitaine, and called the Angevin Empire. Henry II was the first of 13 Plantagenet kings who were to rule England for 300 years. He was universally respected as a just and wise king. He was the first literate king after the Conquest, being able both to read and write. Henry set out to restore the power of the crown and in so doing laid the foundations of a system of government that was to last for centuries. These developments came about partly because the king, having always to be on the move, needed to leave officers he could trust behind him. So successful was he in the case of England that he was able to absent himself for several years at a time, and yet order and justice were maintained. Castles illegally constructed by the barons were demolished and replaced by manor-houses. A knight’s feudal service of 40 days was of little use to Henry, who needed regular soldiers to guard his French possessions. He encouraged his lords to pay a special tax instead of sending him their knights. This allowed him to hire professional soldiers, while the knights remained at home and improved their manors.

Henry II is best remembered for his reform of the courts and the system of law. He sent out his own judges to make regular tours of the country, and any freeman could take a case to them if he didn’t trust the local courts. Most important was Henry’s jury system. In Henry’s times the jurors were witnesses themselves, and no man could be tried unless a jury of 12 men swore that there was a true case against him. This was real progress. In England now there are two kinds of law: statute law, that is Acts made by Parliament, and common law. Common law was first collected together by Henry II. It reflects the changing customs of the land which have been expressed in court judgments through the ages. Henry believed so strongly in the rule of law that he kept no army in England, but laid down the exact weapons and armour that every free man should hold ready for the defence of his country.

What proved a real problem was the king’s relationship with the church and the man who was to become first his chancellor and then his Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket. Many practices of the church courts were an insult to Henry’s rule of law, for they often let even murderers go unpunished. Besides, by the close of the 11th century, the church was undergoing a revolution, asserting the dignity of the priestly office and the power of the popes as direct successors of Christ through St. Peter. The Anglo-Saxon and the Norman church had been at the service of the state. The kings were sacred beings and appointed both bishops and abbots. The king presented them on appointment with a staff and a ring, symbols of their office. The staff, called a crozier, symbolized their role as the shepherd of their flock. They then did homage to the king and received their lands. The struggle to separate the church from the control of the state was to become focused on the one act of the king giving the office holder his staff and ring. In the reign of Henry I a compromise was reached: the king no longer gave the cleric his ring and staff but retained the right to receive his homage. But neither side was happy.

The story of the conflict between Henry II and Thomas Becket, which probably has not only a political but an important human dimension, being also a conflict between personal loyalty and personal convictions, is so dramatic that it served as a source of inspiration for two famous writers, one of whom, the French dramatist Jean Anouilh wrote a play called Becket (1959), and the other, T.S.Eliot, made a verse play Murder in the Cathedral (1935).

The struggle between the church and the state reached a crisis in the reign of Henry II. When the king came to the throne he appointed Thomas Becket to the major administrative post of chancellor. Becket and the king became great friends. In Becket the king saw a means of tidying up relations between church and state. He believed that with his friend as Archbishop of Canterbury the situation could return to how it had been just after the Conquest. In 1161 the opportunity came with the death of the archbishop. On 2 June 1162 Becket was ordained priest and on the following day appointed Archbishop of Canterbury. After that he immediately resigned all his secular offices and changed his style of life to self-denial and humility. Henry, however, failed to recognize that times had changed and his old friend had been trained in the new canon law in which the clergy were exempt from lay interference. Henry decided that criminal clerks must in future be tried by lay courts, for in a church court the worst sentence was to defrock the clerk. Public opinion supported the king and most bishops agreed, but Thomas refused and fled abroad. For 6 years there followed endless attempts to bring about a reconciliation. In July 1170 Becket returned to England. His first act was to excommunicate all the bishops who had taken part in the coronation of Henry’s son as successor in Becket’s absence. The king was seized with fury, crying in an unguarded moment ‘Who will rid me of this low-born priest?’ In all too eager response four knights slipped out of the room, set sail for Kent and on 29 December murdered the archbishop in his own cathedral.

Becket’s tomb in the crypt of Canterbury Cathedral [21] became a shrine at which miracles occurred and soon after, in 1173, the pope canonized him. Canterbury swiftly became the most popular centre of pilgrimage in medieval England. The king himself did penance walking barefoot through the streets of Canterbury and after that gave himself over to being flogged by his bishops and monks. Yet, Henry’s inheritance was splendid: good government in terms of peace, law and order on a scale unknown to any other country in Western Europe at the time.